Recently I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to speak to and interview Nasra Hagi. She is the Founder of Recognize – a wellbeing and training company, she is also a trained Midwife and Nurse and FGM survivor. Nasra currently runs her own business and is passionate about the wellbeing of women and families and has a particular interest in providing support and education around the topic of FGM (female genital mutilation). As you can see, Nasra wears multiple hats, all whilst being a busy Mum to two beautiful young children!

I wanted to understand more about Nasra’s work, her own experience, and what it was that brought her to the work that she does today. Nasra was kind enough to share her own personal story of FGM with me; but before we get into that, let’s get to grips with the basic of understanding what FGM really is.

What is FGM?

FGM is a traditional and harmful practice involving the female genital organs.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), FGM comprises of all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

FGM, female genital cutting (FGC), or female circumcision, as it is also sometimes known, is categorized into 4 different types. The categories are determined by severity and which parts of the genitals are involved.

Type 1 – Clitoridectomy – involves the total or partial removal of the clitoris. This can include the external and/or internal part of the clitoris, and/or removal of the clitoral hood. The clitoris is the sensitive part of the genitals providing female sexual pleasure when stimulated.

Type 2 – Excision – involves type 1, plus the total or partial removal of the inner and/or outer labia.

Type 3 – Infibulation – the narrowing of the vaginal opening with the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting, repositioning or sewing together of the inner and/or outer labia, leaving a small hole for urination and menstruation. This is done with or without the removal of the clitoral gland, as in type 1.

Some women with FGM type 3, must undergo the process of deinfibulation, which involves the practice of cutting the sealed vaginal opening. This is performed to improve the health and wellbeing of the woman and may be necessary to facilitate sexual intercourse or childbirth.

Type 4 – Comprises of all other harmful practices to the female genitals for non-medical purposes, for example piercing, scraping, pricking or cauterising.

Where in the world is FGM prevalent?

It is estimated that over 200 million women and girls worldwide are living with the consequences of the harmful and unacceptable practice of FGM, with millions more being subjected to the procedure every year.

It is important to understand, that there are NO medical benefits, and therefore no justification for the practice of FGM. It is recognised internationally as a violation of human rights and form of child abuse. The practice is usually performed without consent, and without full knowledge of what the procedure entails.

It is typically performed for cultural and social reasons by traditional ‘cutters’ or circumcisers, in countries where this practice remains commonplace. FGM is a specific form of gender-based violence against girls, which is carried out and promoted generally by older women and performed on their daughters or on younger members of the community. It is seen as a form of societal protection for young girls as they become women. We will learn more on this later in the article.

It is illegal to perform the procedure in the UK, and is also illegal to take a British national or resident out of the country for the purpose of performing FGM elsewhere. You can receive up to 14 years in prison for performing FGM, or for helping one take place.

However, sadly, despite the dangers, the practice remains prevalent in many countries around the world. FGM is still practiced in 31 countries spanning Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

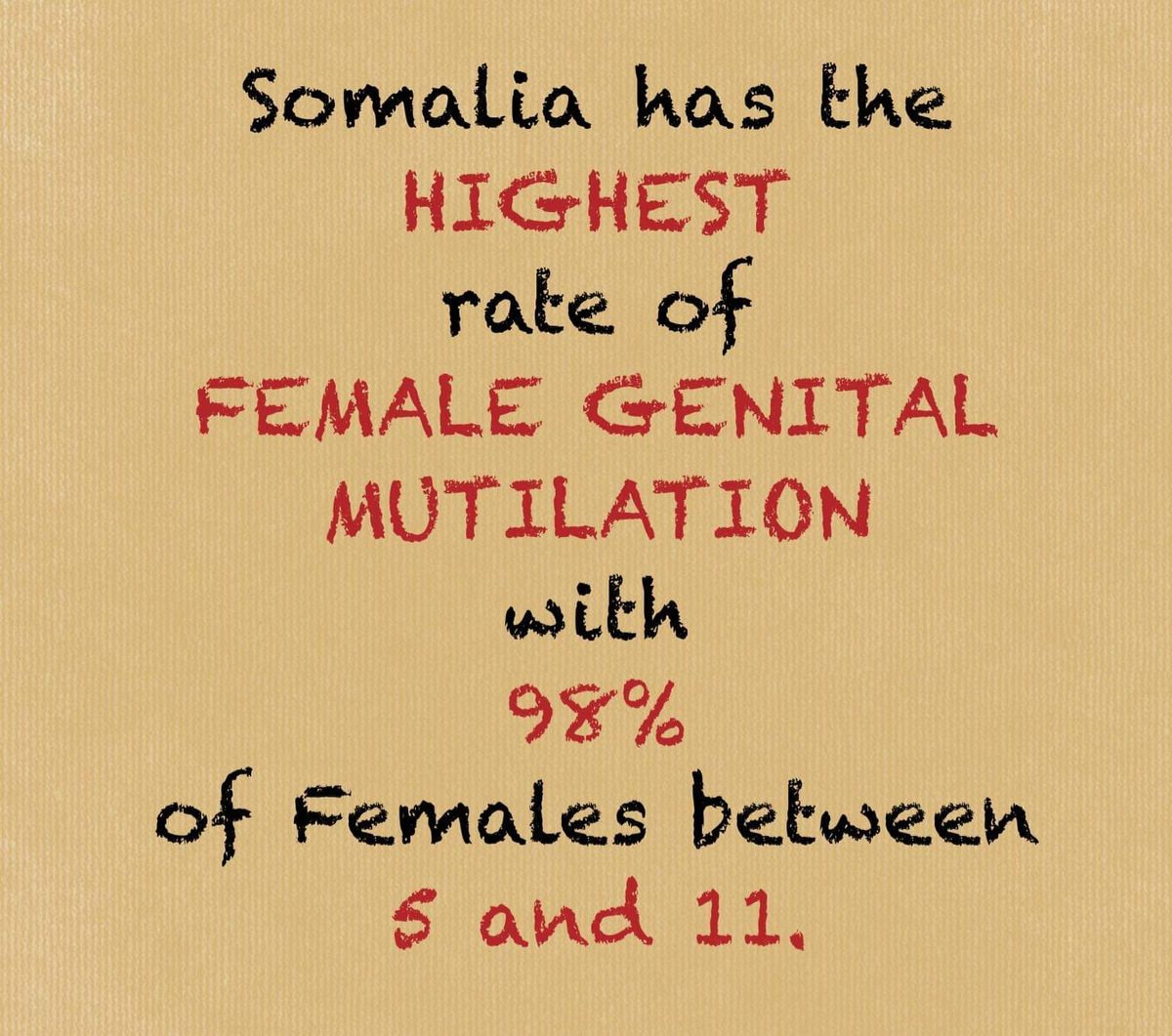

Somaliland, where Nasra is from, is a hot spot for FGM. The rate as of 2021 for women and girls aged between 15-49 was 98%! The practice remains legal, and is complex and culturally deep rooted, making it difficult to erase centuries of tradition. Within these communities the traditional practice of FGM is not seen as a form of abuse but instead seen as way to become socially accepted.

Who is at risk of FGM?

Girls living in communities where FGM is performed are most at risk. This can happen in the UK or abroad.

In the UK, the Home Office have identified women and girls from the following communities as being most at risk:

- Somalia

- Ethiopian

- Sudanese

- Nigerian

- Yemeni

- Indonesian

- Kenyan

- Sierra Leonian

- Egyptian

- Kurdish

Children are also at higher risk of FGM, if other members of their family have also experienced FGM.

When is the procedure performed?

FGM can be performed at different times in a person’s life. It can happen during the newborn phase, or in infancy, but can also happen in adulthood before marriage or during pregnancy.

Typically, FGM is performed before puberty, and commonly anywhere from infancy to 15 years old.

Nasra recalls going through the process of FGM in Somaliland at around 3 years of age, alongside her older sister, who was about 5 or 6 at the time. As two young girls, they were taken by their grandmother for the purpose of FGM (without the consent of their mother). They were led to a practitioner within the community in the capitol of Somaliland, Hargeisa, who performed the surgery. As they were so young, neither Nasra or her sister, fully understood what the procedure involved, or how it would take place. They were led to believe that it was something positive ‘just a little cut down there’, that would lead to acceptance, and that would be celebrated afterwards.

Usually, a big party is hosted at the girl’s parents house the day before the surgery. It is an event, not unlike a festival or ceremony in its feel, not just for the family, but for the community. Friends and family are invited, and new shoes and clothes are bought for the girl to wear on her day. She is made to feel special with jewellery, gold and sometimes henna. Visitors will bring special foods, sweets and money. It is celebrated with love and joy, in recognition of the girl’s passing into womanhood, after which, she will be considered a ‘real’ woman. The celebration involves singing, dancing and eating.

It may be celebrated by others, however Nasra describes the process as ‘the most horrific pain’, she has ever experienced.

The recovery from the initial surgery can take between 4-6 weeks but will vary from person to person.

No health benefits, only harm

FGM holds no health or medical benefits for women or children, only harm. The process is harmful and dangerous and can have serious short and long-term consequences. These effects can be both physical and emotional.

FGM is often performed by individuals with no medical training. It is usually performed by traditional circumcisers who are held in high esteem within their communities. It is normally performed without anaesthesia, analgesia or antibiotics, and often with non-sterile equipment or inadequate tools.

Nasra described how many of the traditional practitioners are usually women of an older generation, who’s eyesight is often poor. They are unlikely to have eyeglasses and therefore may not be able to perform the surgery accurately. Poor visibility combined with additional blood loss cause by inaccuracy, can obviously cause problems during the initial procedure and lead to further complications down the road.

FGM complications

The trauma of this barbaric procedure does not end with the surgery, the consequences of the procedure can be lifelong, and may include any of the following complications:

- Constant pain

- Hemorrhage

- Poor healing

- Tissue damage and scar tissue

- Pain and difficulty having sex, lack of sexual desire or pleasure

- Problems with urination, including frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- Incontinence due to tears in the bladder or rectum, or fistulas

- Bleeding, cysts and abscesses

- Problems with menstruation

- Frequent infections

- Depression, anxiety, flashbacks, sleep issues, nightmares and self-harm

- Corrective or further surgeries

- Problems during childbirth which can be life-threatening for both the mother and her baby

Despite the dangers, why is FGM still performed?

The traditional practice of FGM is complex and multi-faceted. It is deeply engrained within the communities where FGM practice remains. This makes it very difficult to change the beliefs and cultures which have existed for centuries.

It is not as simple as just introducing legislation within these countries. It will take more than legislation to stop this practice from being performed.

Many believe that FGM is performed on a religious basis, however the practice of FGM pre-dates the major faiths and is not required by any religion.

The tradition is so strong that it goes beyond a mother’s natural instincts to protect their daughters. Most women who allow their daughters to have FGM, have been through the process themselves, and therefore know what is to come. The fear of not conforming to the norm, is so strong, as it potentially means discrimination, stigma, shame and dishonour to the family. It can lead to girls and women being ostracized, shunned or isolated from the support system of their community or society, which would lead to poor marriage prospects. Nasra explains that a family will often not marry a woman into the family who has not had FGM performed, leaving prospects for these women bleak.

Why is this your area of interest or your passion?

The effects of FGM are widespread. Nasra feels her experience of FGM, until recently, gave her a lack of general confidence in her life, and she feels this is a common theme amongst those who have had it done. She describes feeling like an ‘invisible’ person. She also feels women experience a constant level of shame and feeling of never being fully accepted as a person.

She feels her experience made her accept many things in life to be normal, which were not. As FGM is a form of abuse, she believes having accepted one level of abuse, she was more susceptible to other forms of abuse. She disclosed to me that she had previously experienced domestic violence, as ‘your brain is wired to accept abuse’.

Nasra moved from Somaliland to Sweden and then on to England. She believes, that had she not have moved from her country of birth, she would still not know or understand the realities and truths about FGM, as FGM is not discussed or talked about openly. Most victims of FGM, are not aware that FGM is a form of abuse, and so the practice is not even questioned.

The truths are not being spoken about, especially in the smaller communities. Nasra, only found out that FGM was not beneficial to health in 2001, when attending an Arabic class in Birmingham, where her teacher informed her of the concerns. She believes, had she still have been in Somaliland, she would probably still believe that FGM was healthy for you, and that the process would have continued through the generations. This is how the practice cycles-why change something you don’t know is wrong?

Nasra tells how the trauma of her own procedure has led her to make different choices for her own daughter.

Why do we need greater awareness of FGM?

With more and more people being displaced around the world due to war, poverty or in seek of asylum, as professionals we need to be aware of FGM, now maybe more than ever. With people moving around the world, potentially from countries and communities where FGM is prevalent, we are likely to come across more and more cases of FGM in the women and children we care for in nurseries, schools, GP surgeries and across maternity services.

What is your hope for the future? – for women and midwives?

FGM is based around custom and ritual, and the fear of judgement from the community.

As we’ve discussed, the reasons behind FGM are complex, and change is always slow. However, a change in attitudes and cultural shifts will only stem from education and knowledge within these practicing communities.

This is what led Nasra to the work that she does today, where she provides training and support for professionals and FGM survivors.

Do you see a world one day where FGM doesn’t exist?

It will take a long time for FGM to be eradicated completely. It may take 10, 20, 50 years for things to change. When I asked Nasra this question, she felt that if FGM wasn’t performed on girls and women, there would be a completely different generation of women who felt able to shine in their true light and power, and that the world would be a very different place.

Safeguarding against FGM

Nasra created the course she now teaches (see below), in response to a growing need for greater FGM awareness and change within our communities. The wider the knowledge base of this issue, the more able we are to break down the silence that has allowed FGM abuse to continue. She believes doing this work is now aligned to her true passions in life, and is also helping her through her own process of self-resilience and healing.

The Safeguarding Against FGM course will cover:

- Previously fully accredited course

- Identification of 4 different types of genital mutilation as defined by WHO

- How to recognise when FGM has occurred

- Asking the right questions about FGM

- Safeguarding procedure

- Community considerations where FGM has been raised as an issue

- Simple mnemonics to help you retain the information you’ve received.

- FGM and Covid

- FGM and the Law

If you would like to find out more about Nasra’s course, please click here.

What to do if you think you are at risk of FGM, or are worried about someone you know?

- The NSPCC, has an FGM helpline you can call on 0800 028 3550 at any time – it’s free and you don’t have to tell them your name (or email fgmhelp@nspcc.org.uk)

- FORWARD, which can give you information and one-to-one support – you can call them on 020 8960 4000 (Monday to Friday from 9.30am to 5.30pm) or email support@forwarduk.org.uk

- UK has more information on what to do if you know somebody at risk including what to do if you think she might have been taken abroad.

If you’re a health or social care professional or a teacher

You’re legally obliged to report cases where you know, or have reason to suspect, that FGM has been carried out and the victim is under 18 years old.

For anyone who is interested in learning more or would like support with enrolment they can contact someone in our team on info@recognizeltd.co.uk